Unit 3: Advanced Topics & Disease Prevention¶

Chapter 3.19: Cancer Risk Reduction¶

[CHONK: 1-minute summary]

What you'll learn in this chapter:

- Why cancer belongs in a longevity certification. And how to discuss it without fear-mongering

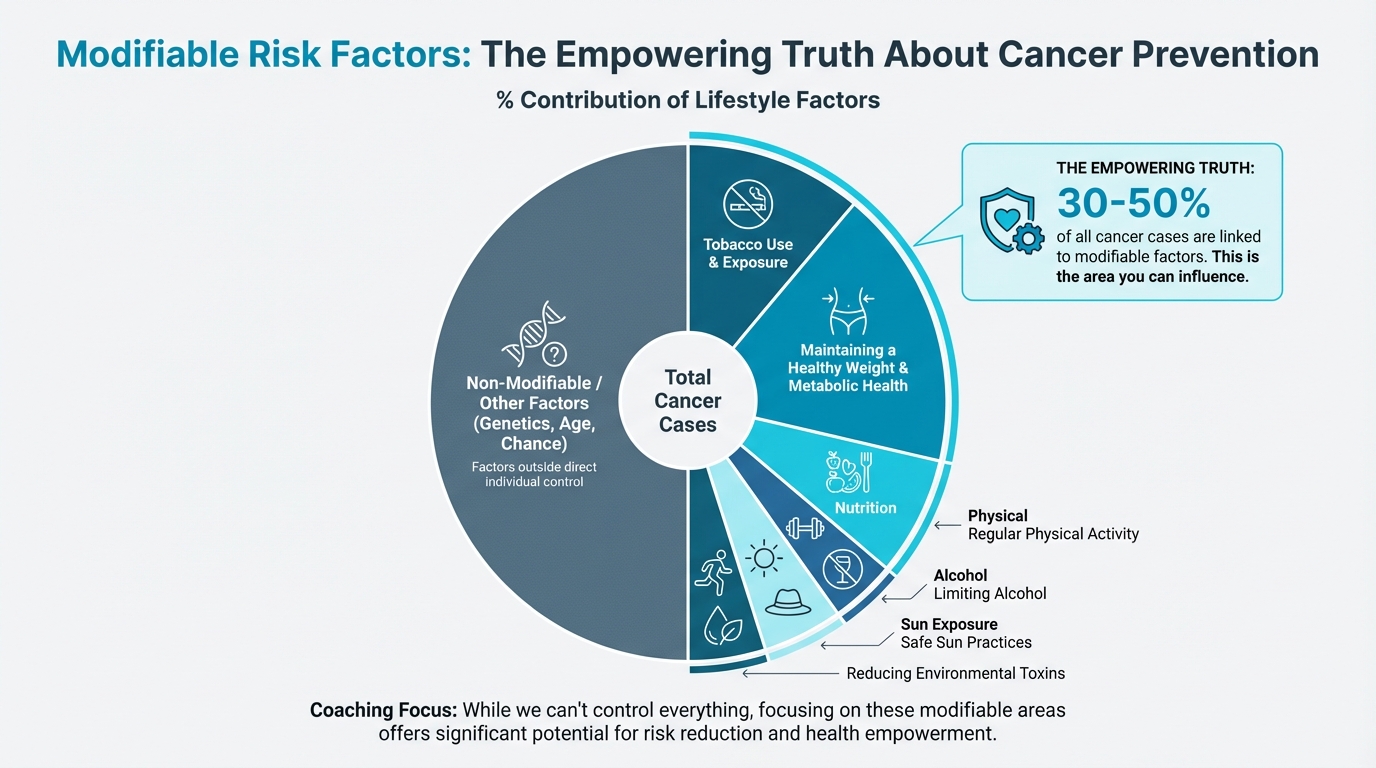

- The empowering truth: 30-50% of cancer cases are linked to modifiable lifestyle factors

- Which lifestyle factors have the strongest evidence for reducing cancer risk

- How metabolic health connects to cancer prevention (connecting your Unit 2 learning)

- Cancer screening basics for educational awareness, without recommending specific tests

- When genetics matter and when to refer clients for genetic counseling

- Scope-safe language patterns for cancer-related coaching conversations

Figure: % contribution of lifestyle factors

The big idea: Cancer is an emotionally charged topic. Your clients may fear it, have family members affected by it, or wonder what they can do to lower their risk. The empowering news is that a substantial portion of cancer risk is within their control. This chapter equips you to discuss cancer prevention through a lens of empowerment, not fear. It focuses on what clients CAN do while maintaining crystal-clear boundaries about what requires physician guidance. You're not here to diagnose, screen, or recommend tests. You're here to help clients build the lifestyle foundations that research shows can meaningfully reduce risk.

[CHONK: Cancer: What Coaches Need to Know]

Why cancer is in this certification¶

If you're thinking, "Wait, cancer? Isn't that outside coaching scope?", you're asking exactly the right question.

You're correct that diagnosing cancer, recommending screening tests, and interpreting results are firmly outside your scope. But here's what isn't outside your scope: helping clients build the lifestyle habits that research consistently links to lower cancer risk.

And that's actually a big deal.

Cancer is the second leading cause of death globally, and it touches nearly every family. Your clients are thinking about it, whether they tell you or not, and many carry quiet fears: about themselves, about loved ones, about family history.

So here's the remarkable news: research from WHO and major cancer research institutions consistently finds that 30-50% of all cancer cases are linked to modifiable risk factors.

Let that sink in. That's not a typo. Up to half of cancers could potentially be prevented (or at least delayed) through lifestyle changes.

In the United States, approximately 40% of cancer cases and nearly 50% of cancer deaths among adults are attributable to modifiable factors. The largest single contributor is tobacco, but even after excluding smoking, about 1 in 5 U.S. cancers are linked to excess body weight, physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, and alcohol.

If that number feels both hopeful and a bit overwhelming, that's a normal response.

This is where you come in. The same fundamentals you've been coaching throughout this certification (regular physical activity, healthy body composition, quality nutrition, adequate sleep, stress management) are also cancer prevention strategies. That's encouraging.

| For DIY Learners |

|---|

| Applying this to yourself: Reading about cancer prevention can bring up fear or anxiety. This is an emotionally loaded topic, so it helps to focus on what you can control: the same habits you're already working on for longevity (exercise, healthy eating, good sleep, managing stress) are also the most evidence-based cancer prevention strategies. You don't need a special "cancer prevention protocol." You need to keep building the fundamentals. |

The empowerment frame¶

The most important principle for this entire chapter:

Empowering, not fear-inducing.

Cancer conversations can easily slide into fear territory, especially when media coverage emphasizes frightening statistics and clients may have lost loved ones or carry their own worries. Your job is to be a steady presence who grounds these conversations in what people can actually do.

Key phrases to internalize:

- "What you CAN control..."

- "Reducing risk, not eliminating risk"

- "The research shows meaningful reductions when..."

- "This is something to discuss with your doctor"

What we avoid:

- "If you don't do X, you might get cancer"

- Guarantees or false reassurance

- Minimizing legitimate concerns

- Making screening recommendations

What coaches CAN and CANNOT do¶

Clear boundaries matter. This should match what you learned in Chapter 1.5.

You CAN:

- Share evidence-based information about lifestyle factors and cancer risk

- Help clients implement health behaviors (exercise, nutrition, sleep) that happen to reduce cancer risk

- Support clients emotionally when cancer is on their mind

- Encourage clients to have screening discussions with their healthcare providers

- Help clients follow through on recommendations their doctors have already made

You CANNOT:

- Recommend specific screening tests ("You should get a colonoscopy")

- Interpret screening results or lab work

- Provide guidance on cancer treatment

- Suggest specific protocols for "cancer prevention"

- Determine whether someone's symptoms warrant concern

The line is simple: education and lifestyle support = yes. Medical recommendations = no.

When in doubt, the phrase is always: "That's definitely something to discuss with your doctor."

Coaching example¶

What NOT to do

Client: "Cancer runs in my family. Which screening tests should I get?"

Coach: "You should get a colonoscopy and ask for a full cancer panel. I think you need to do that ASAP."

A better approach

Client: "Cancer runs in my family. Which screening tests should I get?"

Coach: "I hear why you're thinking about this. I can't recommend specific screening tests or interpret results, but this is definitely something to discuss with your doctor. If you'd like, we can also focus on the lifestyle pieces you can control, like activity, nutrition, sleep, and alcohol, while you have that medical conversation."

[CHONK: Modifiable Risk Factors]

The lifestyle factors you can actually address¶

Here's where the empowerment gets concrete: below are the major modifiable risk factors for cancer, ranked roughly by the strength of evidence and magnitude of impact.

Tobacco: The #1 modifiable factor¶

We'll address this briefly because you likely know it already, but the numbers are worth stating: cigarette smoking alone accounts for approximately 20% of all U.S. cancer cases and about 30% of cancer deaths.

Smoking causes cancers of the lung, mouth, throat, esophagus, stomach, kidney, bladder, pancreas, and more. The carcinogenic mechanisms are multiple: direct DNA damage, chronic inflammation, and impaired immune function.

What NOT to do:

"You just need to quit. Smoking is terrible for you."

A scope-safe coaching conversation might sound like:

Client: "I know I should quit, but I’ve tried before and it didn’t stick."

Coach: "That makes sense. Nicotine addiction is complex. Would it be okay if we talk about what’s made quitting hardest, and what kind of support would feel realistic right now?"

Client: "Yeah. I think I need more structure this time."

Coach: "We can absolutely work on the day-to-day habits and triggers. And if you’re open to it, we can also loop in your physician, a cessation program, or behavioral health so you’re not doing this alone."

Alcohol: The carcinogen many don't know about¶

This one surprises people, but the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the cancer research arm of the World Health Organization, classifies alcohol as a Group 1 carcinogen, the highest classification for substances known to cause cancer in humans. That puts it in the same category as tobacco.

What the research shows:

Alcohol has causal links to cancers of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, esophagus, liver, colorectum, and female breast. The mechanisms are well-understood: when you drink alcohol, your body metabolizes it to acetaldehyde, a compound that directly damages DNA, causes mutations, and interferes with DNA repair.

The dose-response relationship is clear and begins at low levels. Research shows:

- Light drinking (less than one drink per day) significantly increases risk for esophageal, colorectal, and breast cancers

- Each additional standard drink per day increases postmenopausal breast cancer risk by approximately 12%

- Heavy drinking raises head and neck cancer risk approximately 5-fold compared to non-drinkers

The "no safe level" evidence:

Here's where we apply our "island of sanity" principle: sharing what the evidence actually shows, not what people want to hear.

Current scientific consensus, including from the WHO, is that no level of alcohol consumption is safe for cancer risk. Risk increases continuously from the first drink. About half of alcohol-attributable cancers in Europe arise from light to moderate consumption.

This doesn't mean every client who has an occasional drink is at imminent risk. It means that from a pure cancer risk standpoint, less is better, and none is best. How clients weigh that against other life factors is their choice to make.

What this means for your client:

What NOT to do:

"You have to stop drinking. There’s no safe level."

A scope-safe conversation might sound like:

Client: "I’ve heard red wine is good for you. Is alcohol actually a problem?"

Coach: "It can be surprising, but alcohol is classified as a known carcinogen by the WHO. From a cancer-risk perspective, risk increases with the amount you drink, and the evidence suggests there isn’t a level that’s truly ‘safe.’"

Client: "So should I quit completely?"

Coach: "That’s your call. My job is to make sure you have accurate information, and then we can talk through what feels doable for you. If you want to reduce your intake, I’m happy to help you map out a plan."

Body composition and visceral fat¶

You covered metabolic health extensively in Unit 2, and here's how it connects to cancer.

Excess body fat, particularly visceral (abdominal) fat, is linked to increased risk for at least 13 types of cancer. These include breast (postmenopausal), colorectal, endometrial, esophageal, kidney, liver, gallbladder, stomach, pancreatic, ovarian, thyroid, multiple myeloma, and meningioma.

The CDC notes that these obesity-linked cancers account for approximately 40% of all U.S. cancer diagnoses each year.

Mechanisms matter:

Why does excess fat increase cancer risk? The pathways you learned in Unit 2 are directly relevant:

| Mechanism | How It Promotes Cancer |

|---|---|

| Chronic inflammation | Visceral fat tissue becomes infiltrated with immune cells that release inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β), creating a tumor-promoting environment |

| Hyperinsulinemia | Elevated insulin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) activate growth pathways (PI3K/Akt/mTOR) that promote cell proliferation and inhibit apoptosis |

| Adipokine imbalance | Increased leptin promotes proliferative signaling; decreased adiponectin removes its tumor-suppressive effects |

| Elevated estrogens | Adipose tissue contains aromatase, which converts androgens to estrogens, particularly relevant for hormone-sensitive cancers like breast and endometrial |

You don't need to memorize every mechanism; the key takeaway is that less visceral fat and better metabolic health mean lower cancer risk.

Risk varies by site:

Meta-analyses provide specific risk estimates. Compared to normal weight:

- Endometrial cancer risk increases approximately 76% with overweight/obesity

- Kidney cancer risk increases approximately 50%

- Liver cancer risk increases approximately 52%

- Colorectal cancer risk increases approximately 27%

- Postmenopausal breast cancer risk increases approximately 13%

The good news: weight loss helps:

Studies of bariatric surgery provide the strongest evidence: patients who undergo bariatric surgery show a 38% reduction in overall cancer risk, with particularly large reductions for endometrial (62% lower), liver (65% lower), and colorectal (37% lower) cancers.

Lifestyle-based weight loss shows similar direction, though the magnitude is harder to quantify because sustained large weight loss is difficult to achieve through lifestyle alone. The Look AHEAD trial of intensive lifestyle intervention showed a trend toward 16% lower obesity-related cancer incidence, though the study wasn't powered to detect statistical significance for cancer endpoints.

What this means for your client:

The metabolic health work you're already helping clients with IS cancer prevention work. When you help someone improve body composition, reduce visceral fat, and improve metabolic markers, you're simultaneously addressing cancer risk.

Why this conversation is hard¶

Here's the uncomfortable reality: talking about weight and cancer risk can feel like walking a tightrope.

On one side, there's real, actionable information: body composition genuinely affects cancer risk, and changes genuinely help. On the other side, there's the risk of adding shame, fear, or blame to an already emotionally loaded topic.

Many clients carry complex histories around weight. Adding "cancer prevention" to the reasons they "should" lose weight can feel like another layer of pressure, another way they're failing. And for clients who've already had cancer, the implication that their weight contributed can feel devastating.

So how do you navigate this?

Lead with what's controllable and actionable, not what's fixed. Focus on metabolic health markers and behaviors, not just the number on the scale. And remember: your job isn't to scare people into change; it's to help them find sustainable paths forward. The goal is empowerment, not anxiety.

Physical activity¶

If you could bottle the cancer-prevention effects of exercise and sell it as a pill, it would be worth billions.

What the research shows:

Higher physical activity is consistently associated with lower incidence of multiple cancers. The benefits appear across numerous cancer sites:

| Cancer Site | Risk Reduction (High vs. Low Activity) |

|---|---|

| Colon | ~7-25% lower risk |

| Breast | ~10-20% lower risk |

| Endometrial | ~18% lower risk |

| Liver | ~17% lower risk |

| Kidney | Variable, substantial reductions |

| Lung | ~12-22% lower risk |

| Bladder | ~32% lower risk |

Meeting guideline-level activity (approximately 150-300 minutes per week of moderate activity) is associated with 6-29% lower risk across several cancer types. The benefits appear dose-dependent. More activity generally means more protection, though with diminishing returns at very high levels.

Mechanisms:

Exercise likely reduces cancer risk through multiple pathways:

- Insulin/IGF signaling: Exercise improves insulin sensitivity and reduces circulating insulin and IGF-1

- Inflammation: Regular activity reduces chronic systemic inflammation

- Sex hormones: Exercise can lower circulating estrogens, particularly relevant for breast and endometrial cancer

- Immune function: Exercise enhances immune surveillance

- Direct effects: Myokines (muscle-derived signaling molecules) may have anti-tumor properties

Sedentary time matters independently:

Research shows that sedentary behavior increases cancer risk independent of physical activity levels. High sedentary time is associated with:

- 29% higher ovarian cancer risk

- 29% higher endometrial cancer risk

- 25% higher colon cancer risk

This means that even for clients who exercise regularly, reducing prolonged sitting time may provide additional benefit.

What this means for your client:

What NOT to do:

"You need to exercise because it prevents cancer."

A more helpful approach might sound like:

Client: "I know I should work out, but I just can’t seem to stick with it."

Coach: "You’re not alone. Would you be open to starting with something smaller that’s easier to repeat, like two 10-minute walks most days, and then building from there?"

Client: "That feels more doable."

Coach: "Great. And just so you have the full picture, consistent activity supports a lot of things at once, including long-term cancer risk. We’ll focus on a plan you can actually sustain."

Diet and inflammation¶

The diet-cancer relationship is complex, and certainty is lower than for the factors above. But several patterns emerge from large-scale research.

What appears protective:

- High fruit and vegetable intake (associated with lower risk for several cancers)

- Fiber intake (particularly for colorectal cancer)

- Dietary patterns rich in whole foods (Mediterranean-style patterns show consistent associations with lower cancer incidence)

What appears to increase risk:

- Processed meat (IARC classifies as Group 1 carcinogen; linked to colorectal cancer)

- Red meat (IARC classifies as Group 2A, probably carcinogenic; linked to colorectal cancer)

- Ultra-processed foods (emerging evidence links higher intake to increased cancer incidence)

- High glycemic load diets (likely through metabolic pathways discussed above)

Important context:

Diet research is challenging. People who eat healthier also tend to have other healthy behaviors, making causation difficult to establish. Effect sizes for individual foods are generally modest compared to factors like smoking, alcohol, and obesity.

The practical takeaway: whole-food dietary patterns that you'd recommend for metabolic health are also the patterns associated with lower cancer risk. You don't need separate "cancer prevention diets". The fundamentals apply.

| Modifiable Risk Factor | Impact on Cancer Risk | Strength of Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Tobacco | ~20% of all cancers; ~30% of cancer deaths | Very Strong |

| Alcohol | Causes 7+ cancer types; dose-dependent risk from first drink | Very Strong |

| Excess body fat | Linked to 13 cancer types; ~40% of diagnoses are obesity-related cancer types | Strong |

| Physical inactivity | Higher activity = 6-29% lower risk across multiple sites | Strong |

| Diet | Processed meat, low fiber, ultra-processed foods associated with higher risk | Moderate |

| Sun/UV exposure | Major cause of skin cancers (not covered in detail here) | Very Strong |

[CHONK: The Metabolic-Cancer Connection]

Connecting your Unit 2 learning¶

Everything you learned in Unit 2 about metabolic health has direct implications for cancer risk. Let's make those connections explicit.

Insulin, insulin resistance, and cancer¶

Insulin resistance isn't just about diabetes risk. It's a cancer risk factor.

The mechanisms are well-characterized:

- Hyperinsulinemia promotes tumor growth: Elevated insulin activates insulin receptors on cells, triggering growth and proliferation pathways (PI3K/Akt/mTOR, MAPK). Cancer cells often overexpress insulin receptors.

- IGF-1 amplification: Insulin resistance increases bioavailable IGF-1, a potent growth factor that promotes cell division and inhibits apoptosis.

- Fuel supply: High insulin states increase availability of glucose and fatty acids that cancer cells can use for energy and growth.

The epidemiological evidence:

Type 2 diabetes is associated with approximately 10-17% higher overall cancer risk, with particularly elevated risks for pancreatic, liver, and endometrial cancers. People with diabetes have approximately 20-30% higher cancer mortality.

Metabolic syndrome (the cluster of insulin resistance, central obesity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension) is associated with:

- ~2-fold increased risk of endometrial cancer

- Higher recurrence and mortality in breast cancer survivors

- Reduced remaining life expectancy after cancer diagnosis

An important distinction:

Research using genetic techniques (Mendelian randomization) suggests that elevated fasting insulin, not fasting glucose, may be the causal driver for colorectal cancer risk. This aligns with the mechanistic understanding: it's the hyperinsulinemia that matters most, not just blood sugar levels.

Chronic inflammation¶

You learned about inflammation as a metabolic disruptor. It's also a cancer promoter.

Chronic low-grade inflammation, often called "inflammaging", creates an environment where cancer can initiate and progress. The NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways, when chronically activated by inflammatory signals, promote tumor survival and growth.

Research estimates that approximately 15-25% of cancers arise from or are promoted by chronic inflammatory conditions.

The sources of chronic inflammation relevant to your coaching work include:

- Visceral adiposity (inflamed fat tissue)

- Poor metabolic health

- Chronic stress

- Poor sleep

- Sedentary behavior

- Diet high in processed foods

You don't need to remember every pathway, only that chronic inflammation and poor metabolic health can raise cancer risk.

| For DIY Learners |

|---|

| Applying this to yourself: Your metabolic health markers (fasting insulin, HbA1c, inflammatory markers like CRP) aren't just diabetes risk indicators. They're part of your cancer risk picture too. If you have access to these numbers from recent bloodwork, take a look. Are you in optimal ranges? If not, the lifestyle changes that improve metabolic health (and which you're already learning about in this certification) are also cancer-protective. This isn't about adding another thing to worry about: it's about recognizing that the fundamentals you're already working on serve multiple purposes. |

What this means for your client¶

Here's the empowering synthesis: metabolic health coaching IS cancer prevention coaching.

When you help a client:

- Improve insulin sensitivity through exercise and nutrition → you're reducing cancer risk pathways

- Reduce visceral fat → you're reducing inflammation and cancer-promoting signals

- Build muscle mass → you're improving metabolic health and potentially benefiting from myokine effects

- Manage stress and improve sleep → you're reducing inflammatory burden

You don't need to frame it as "cancer prevention" in every conversation. That could be anxiety-provoking for some clients. But you can feel confident that the fundamental work of helping people live healthier lives has implications far beyond what the scale shows.

Coaching in practice: When a client asks about cancer prevention¶

The scenario: A client shares that a close relative has been diagnosed with cancer and asks what they can do to lower their own risk.

Client: "My aunt was just diagnosed with breast cancer. It's got me thinking: what can I do to lower my own risk?"

What NOT to do:

❌ Jump straight into detailed risk calculations or start recommending specific screening tests or genetic panels.

Why this doesn't work: You're not the one to assess their personal medical risk, and making specific medical recommendations steps outside your scope of practice and can increase anxiety.

What TO do:

✅ Treat it as both an emotional moment and a coaching opportunity. Acknowledge the emotion first, then share modifiable risk factors and reinforce appropriate referral.

Coach: "I'm so sorry to hear about your aunt. That must be really hard news." [Pause]

Client: "Yeah. She always seemed so healthy, and now I'm scared it could happen to me."

Coach: "That reaction makes a lot of sense. When something like this happens in the family, it's normal to start wondering what it means for you."

Client: "Exactly. I keep thinking, 'Am I next?'"

Coach: "Would it be okay if we talk about two things: what you can actually influence, and what would be good to bring to your doctor?"

Client: "Yes, please."

Coach: "In terms of what you can influence, the research points to things like staying physically active, maintaining a healthy weight, and being thoughtful about alcohol. Those are all things we can work on together."

Client: "So there is something I can do, it's not just luck?"

Coach: "Exactly. There are no guarantees, but there are real ways to tilt the odds in your favor."

Coach: "For the questions about your personal risk and whether you might need different screening or genetic testing, that's where your doctor (and possibly a genetic counselor) come in. Would it help to think through a few questions you could bring to your next appointment?"

Client: "Yeah, I wouldn't even know how to start that conversation."

Coach: "Great. Let's write down a couple of questions together so you feel more prepared."

Key takeaways:

- Acknowledge the emotional weight first

- Provide empowering, behavior-focused information

- Maintain clear scope boundaries around risk assessment and testing

- Facilitate the appropriate healthcare conversation

[CHONK: Cancer Screening: Educational Awareness]

What coaches should know about screening¶

Clients often ask about cancer screening, like whether they’re “up to date,” whether they should be tested for something specific, and what the latest guidelines actually say. (And yes, it can get confusing fast.)

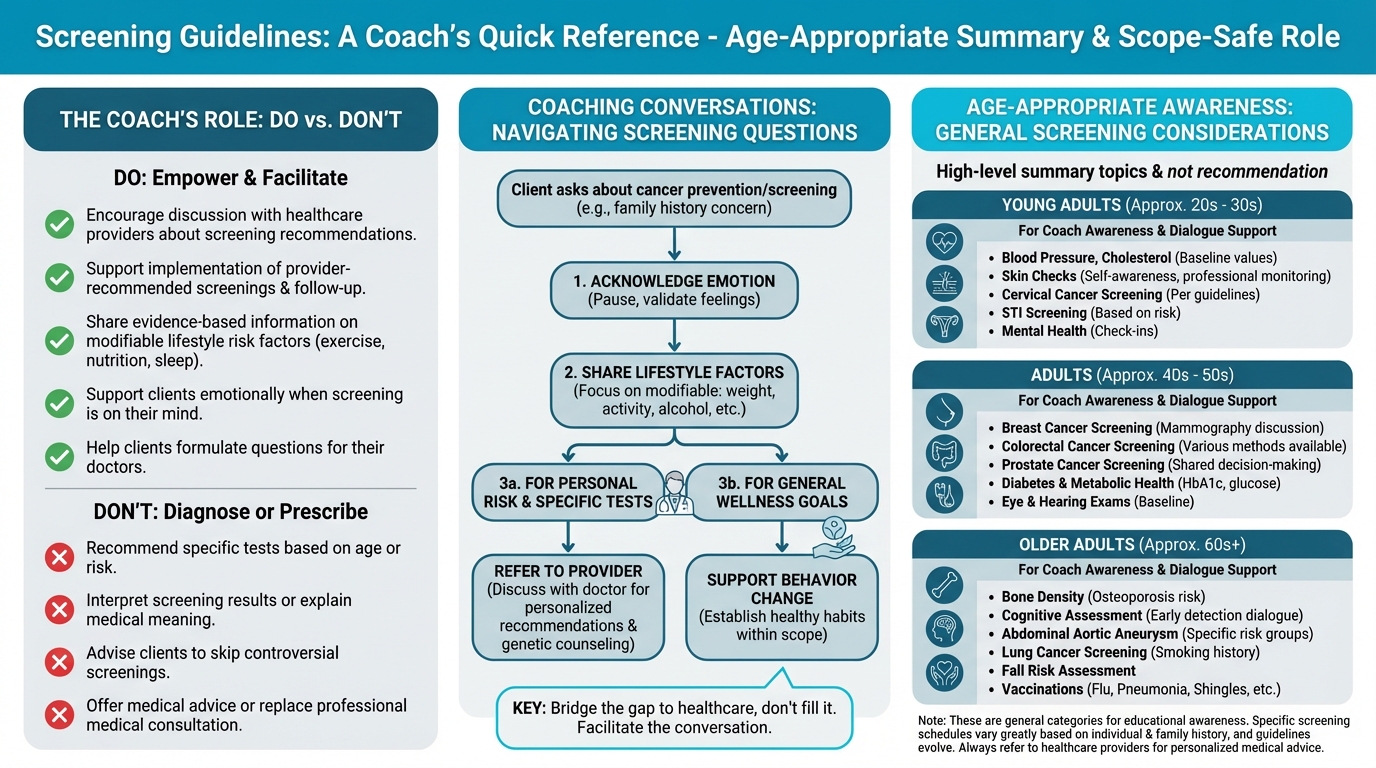

Figure: Age-appropriate screening summary

As a coach, you’re not the person who recommends specific screening tests. That’s in a physician’s lane. What you can do is build enough educational awareness to support calm, informed conversations, and help clients follow through on the decisions they make with their healthcare team. (This is actually a big deal.)

Overview of screening guidelines¶

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) is the primary body that reviews evidence and makes screening recommendations. Their grades range from A (strongly recommend) to D (recommend against), with C (individual decision) and I (insufficient evidence) in between.

Educational overview of common screenings:

| Screening | What It Is | General Population* |

|---|---|---|

| Colonoscopy | A procedure where a physician examines the colon with a camera to detect polyps (precancerous growths) and cancer | USPSTF recommends colorectal screening for adults 45-75 (multiple test options including colonoscopy, stool tests) |

| Mammography | X-ray imaging of breast tissue to detect cancer early | USPSTF recommends biennial mammograms for women 40-74 |

| PSA test | A blood test measuring prostate-specific antigen | USPSTF recommends shared decision-making for men 55-69; recommends against routine screening for men 70+ |

| Cervical (Pap/HPV) | Cervical cell sampling to detect precancerous changes | USPSTF recommends cervical screening for women 21-65 with various test options |

| Skin checks | Clinical visual examination of skin for suspicious lesions | USPSTF: insufficient evidence for routine screening; dermatology groups suggest targeted approaches |

| Ovarian screening | CA-125 blood test or transvaginal ultrasound | USPSTF recommends AGAINST screening average-risk women (no mortality benefit, significant harms) |

| Lung (LDCT) | Low-dose CT scan for high-risk individuals | USPSTF recommends for adults 50-80 with significant smoking history |

*These are general guidelines for average-risk populations. Individual recommendations may differ based on personal and family history. When in doubt, your safest and most helpful move is to point clients back to their healthcare provider for personalized guidance.

Why screening is complicated¶

Screening sounds like a no-brainer: find cancer early, treat it early, save lives. In real life, though, the trade-offs can be more complex. (You’re not imagining it.)

Benefits of screening:

- Can detect cancer at earlier, more treatable stages

- May reduce cancer mortality for certain cancers

- Provides peace of mind for many people

Potential harms:

- False positives: Lead to anxiety, additional testing, and sometimes invasive procedures for conditions that turn out not to be cancer

- Overdiagnosis: Detection of cancers that would never have caused symptoms or death (particularly relevant for prostate and some breast cancers)

- Procedure risks: Colonoscopy carries small but real risks; biopsies can cause complications

- Psychological impact: Living with a cancer diagnosis, even a slow-growing one, affects quality of life

Shared decision-making between patients and physicians matters because the "right" answer depends on personal risk, values, and how someone feels about uncertainty and follow-up testing. You don't need to be the screening expert; you just need to be a steady, supportive presence while your client talks it through with their doctor.

Your role in screening conversations¶

When clients ask about screening, your role is to:

-

Encourage discussion with their physician: “That’s a great question to bring to your doctor at your next visit.”

-

Support informed decision-making: “Screening is one of those areas where the best choice can look different for different people. Your doctor can help you weigh the benefits and risks based on your specific situation.”

-

Help with implementation: If a client’s doctor has recommended a screening, you can help them schedule it, manage anxiety around it, and follow through.

-

Never recommend specific tests: Even if you think someone “obviously” needs a screening, that’s still a medical decision.

What About Advanced Screening?

Some longevity-focused clients may ask about emerging screening technologies they’ve heard about on podcasts or in online communities:

Multi-Cancer Early Detection Tests (like Galleri): These blood tests aim to detect multiple cancers from a single blood draw. Current evidence shows:

- Very high specificity (~99%). Few false positives

- Moderate overall sensitivity (~50%), meaning they miss about half of cancers

- Particularly low sensitivity for early-stage cancers (~17-27% for stage I)

- No evidence yet that they reduce mortality

- Large randomized trials are ongoingWhole-Body MRI: Some wellness centers offer full-body MRI scans. The evidence is concerning:

- Very high rate of incidental findings (up to 95% show something)

- ~30% require follow-up testing

- Only ~1-2% of findings are confirmed cancers

- Major radiology organizations recommend against it for average-risk individuals

- Significant cost ($1,000-$2,500+) typically not covered by insuranceKey point: These technologies should complement, never replace, guideline-recommended screenings that have proven mortality benefits.

[CHONK: Genetics and Cancer Risk]

When genetics matter¶

Some clients have significant family histories of cancer or already know they carry genetic variants that increase their risk. For these clients, the stakes feel higher, and the conversations can be emotionally loaded.

This is territory that requires physician and genetic counselor guidance. But you should understand the basics so you can support these clients and recognize when referral is needed.

What you should know¶

A small but meaningful percentage of cancers are driven primarily by inherited genetic variants:

BRCA1/BRCA2 (Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome)

- Carriers have lifetime breast cancer risk of approximately 65-79%

- Ovarian cancer risk: ~36-53% for BRCA1; ~11-25% for BRCA2

- Occurs in approximately 1 in 500 people in the general population; 1 in 40 in Ashkenazi Jewish populations

- Carriers typically receive enhanced screening (MRI plus mammography) and may consider risk-reducing surgery

Lynch Syndrome (Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer)

- Lifetime colorectal cancer risk up to 52-82%

- Endometrial cancer risk: 40-60% in women

- Accounts for approximately 2-3% of all colorectal cancers

- Carriers typically receive more frequent colonoscopies (every 1-2 years)

What clients may ask:

- "Should I get genetic testing?"

- "Does my family history mean I'm at higher risk?"

- "My mom had cancer at 45. Should I be screened earlier?"

Your role with genetic questions¶

These are referral questions. Every time.

Genetic counselors and physicians specializing in cancer genetics are trained to:

- Evaluate family history patterns

- Determine if genetic testing is appropriate

- Interpret test results

- Recommend tailored screening and prevention strategies

Your job is to recognize when these conversations need to happen and facilitate the referral:

"Given your family history, this is really something to discuss with your doctor. They may suggest you meet with a genetic counselor who can help you understand your personal risk and what options might be available. Would it help to think through how to bring this up at your next appointment?"

Helping clients think about family history¶

You can appropriately ask about family history to understand context, but interpretation belongs to healthcare providers.

Red flags that suggest a client should discuss genetic counseling with their doctor:

- Multiple close relatives with the same cancer

- Cancer diagnosed at unusually young ages (before 50)

- Relatives with rare cancers

- Known genetic mutations in the family

- Ancestry associated with founder mutations (e.g., Ashkenazi Jewish heritage for BRCA)

Resource for clients:

For clients interested in learning more about genetics and health, Precision Nutrition has developed a thorough e-book on genetic testing that provides balanced, evidence-based information: Precision Nutrition's Genetic Testing E-Book.

[CHONK: Coaching Cancer Prevention]

Practical skills for cancer-related conversations¶

Cancer conversations require a special blend of empathy, accurate information, and clear boundaries. Here are practical approaches for common scenarios.

Managing cancer anxiety¶

Some clients carry significant anxiety about cancer, whether due to family history, health-related anxiety in general, or previous scares. In those moments, your job is to be a calming, grounded presence: don’t dismiss their concerns, and don’t amplify them either.

Acknowledge without amplifying:

Client: "I'm constantly worried about getting cancer. My grandmother died of it, and I feel like it's just a matter of time."

Coach: "I can hear that this weighs on you. That's understandable given what you've seen in your family. Can I share what the research actually shows about what's in your control? Because the picture is more empowering than it might feel right now."

Ground in evidence:

When anxiety is high, concrete facts can be anchoring:

- "The research shows that 30-50% of cancers are linked to modifiable factors, meaning a significant portion of risk is things you can influence."

- "The lifestyle work you're doing (staying active, maintaining a healthy weight, eating well), this IS cancer prevention work."

Refer when appropriate:

Health anxiety that significantly impacts quality of life may warrant referral to a mental health professional. If a client is:

- Persistently preoccupied with cancer, to the point that it’s hard to focus on other parts of life

- Avoiding activities due to cancer fears, or experiencing panic or severe distress when the topic comes up

...gently suggest they discuss these feelings with a counselor or therapist.

Supporting clients with family history¶

Clients with strong family histories of cancer need:

1. Validation: Their concerns are legitimate, not irrational

2. Empowerment: There are still things they can control

3. Appropriate referral: Their screening and prevention may need to be different

What NOT to do:

❌ Minimize or predict: "Try not to worry. You’ll probably be fine," or "With your family history, you’re basically guaranteed to get it."

A more helpful approach:

Client: "Cancer runs in my family. Should I be really worried?"

Coach: "Your family history is worth taking seriously, and I'm glad you're bringing it up. Have you talked with your doctor about whether genetic counseling or a different screening schedule makes sense for you?"

Client: "Not yet. I’m not even sure what to ask for."

Coach: "We can absolutely map out a few questions for that appointment. And in the meantime, the lifestyle factors we're working on still matter for everyone, including people with a family history. We're not powerless here."

Clients with personal cancer history¶

If you work with cancer survivors, additional sensitivity is needed. These clients carry experiences that shape everything about how they relate to their health.

- Don't assume they want to talk about it: Let them lead. Some people want to process; others want to move on.

- Recognize the complexity: They may have treatment-related side effects, fears of recurrence, or complicated feelings about their bodies. All of this is normal.

- Focus on their current goals: Unless they bring up cancer, focus on what they came to coaching for. They're more than their diagnosis.

- Know your limits: Cancer survivorship involves real medical complexity. Collaborate with their oncology team; don't freelance. This is one area where humility isn't just nice; it's essential.

Coaching in practice: Handling "should I be worried?" questions¶

The scenario: A client brings up a vague symptom and directly asks whether they should worry about cancer.

Client: "I've been having some digestive issues lately. Should I be worried about cancer?"

What NOT to do:

❌ Try to reassure or diagnose: "I'm sure it's nothing," or "That does sound concerning."

Why this doesn't work: You're not qualified to evaluate symptoms, and guessing (in either direction) can increase anxiety or delay needed care. It also steps well outside your scope of practice.

What TO do:

✅ Treat this as a referral moment and help them prepare for a medical conversation.

Coach: "I'm not able to evaluate symptoms like that. That's really something for your doctor."

Coach: "How long has this been going on, and how is it affecting your day-to-day life?"

Client: "A few weeks. It's not awful, but it's definitely bothering me, and my mind always goes to the worst-case scenario."

Coach: "That's really understandable. When our bodies do something different, it's easy to jump to scary possibilities."

Coach: "Have you had a chance to mention this to your doctor yet?"

Client: "No, I keep putting it off because I'm afraid of what they'll say."

Coach: "Totally fair. At the same time, talking to them is the best way to get real answers instead of living with 'what ifs.'"

Coach: "I'd encourage you to bring this up. Digestive issues can have all kinds of causes, and your doctor can help figure out what's going on."

Coach: "Would it help if we jot down a few notes about your symptoms and practice how you might bring it up, so the conversation feels a little easier?"

Client: "Yeah, that would make me feel better about going in."

Key takeaways:

- You don't reassure or alarm, and you don't recommend specific tests.

- You don't dismiss their concern, and you consistently facilitate the healthcare conversation.

Coaching in practice: The fundamentals-first conversation¶

The scenario: A client feels overwhelmed by all the things they hear "cause cancer" and wonders how they can possibly avoid every risk.

Client: "I keep reading about all these things that cause cancer, and it feels overwhelming. How can I possibly avoid it all?"

What NOT to do:

❌ Add to the overwhelm by listing every possible carcinogen or giving them a long list of advanced "biohacks" to chase.

Why this doesn't work: It reinforces a sense that everything is dangerous and can leave clients frozen, anxious, or focused on minor details instead of the big levers.

What TO do:

✅ Normalize their feelings and gently redirect their attention to the handful of fundamentals that account for most modifiable risk.

Coach: "I hear you, it can feel like everything is dangerous when you start reading about cancer risk."

Client: "Yeah, one article says something is bad and the next says it's fine, so I don't know what to believe."

Coach: "Totally. It can start to feel like nothing is safe."

Coach: "Here's what helps me think about it: there are a handful of factors that account for the vast majority of modifiable risk. Things like smoking, alcohol, body composition, physical activity, and basic nutrition patterns. Those are the big ones."

Client: "So if I focus on those, I don't have to obsess over every little thing?"

Coach: "Exactly. The good news is you don't need to be perfect at everything, and you don't need to eliminate every theoretical risk. You just need to be reasonably consistent with the fundamentals."

Coach: "And honestly? The fundamentals are the same things we'd focus on for energy, for mood, for metabolic health, for feeling good. It's not a separate 'cancer prevention protocol.'"

Client: "That actually feels a lot more manageable."

Coach: "Great. What if we pick one of those big areas to start with and choose one small, realistic change you could make this week?"

Key takeaway: When clients feel overwhelmed, help them zoom out and focus on consistent fundamentals rather than chasing every possible risk.

Scope-safe language patterns summary¶

| Instead of... | Try... |

|---|---|

| "You should get screened for..." | "That's something to discuss with your doctor" |

| "This symptom might mean..." | "Any symptoms like that are worth mentioning to your doctor" |

| "Don't worry, you probably don't have cancer" | "I can't evaluate that, but your doctor can help you understand what's going on" |

| "You need to do X to prevent cancer" | "Research shows that X is associated with lower cancer risk" |

| "Your family history means you'll probably..." | "Your family history is worth discussing with your doctor or a genetic counselor" |

Deep Health integration¶

Cancer risk, and cancer conversations, touch multiple Deep Health dimensions:

Physical: This is the primary domain for this chapter. Body composition, exercise, nutrition, and metabolic health all directly influence cancer risk through biological pathways, which means the fundamentals deliver the greatest impact.

Emotional: Cancer is an emotionally loaded topic. Clients may carry fear, grief, or anxiety related to cancer, their own experiences or those of loved ones. Creating space for these emotions while remaining grounded and helpful is essential coaching work.

Mental: Understanding risk versus certainty is cognitively challenging. Helping clients think clearly about probabilistic information, "reducing risk is not eliminating risk," supports their mental well-being and decision-making.

Existential: Cancer often prompts reflection on mortality, meaning, and what matters. These conversations, when they arise, deserve presence and respect. You don't need to have answers; you need to be a thoughtful witness.

Relational: Cancer affects families. Clients may be navigating conversations with relatives about screening, genetic testing, or lifestyle changes. Supporting these relational dynamics can be part of your work.

Environmental: Carcinogen exposure in the environment (workplace, products, pollution) is real but largely outside coaching scope. If clients have specific environmental concerns, those warrant physician discussion.

[CHONK: Study guide questions]

Study guide questions¶

Here are some questions to help you think through the material and prepare for the chapter exam. They’re optional, but we recommend answering at least a few as part of your active learning process. If you get stuck, that’s normal, and even a rough first pass is useful.

-

Why is "empowering, not fear-inducing" the right frame for cancer conversations, and how should it shape your language choices?

-

Approximately what percentage of cancers are linked to modifiable lifestyle factors, and which factors tend to matter most?

-

How does insulin resistance connect to cancer risk, and how does that relate to what you learned in Unit 2?

-

A client asks you which cancer screening tests they should get. What’s the appropriate response, and why?

-

What family history patterns might suggest a client should discuss genetic counseling with their doctor?

-

How would you explain to a client that "reducing risk is not eliminating risk" while still being encouraging?

Self-reflection questions:

-

Are you current on your age-appropriate cancer screenings, and if not, what’s getting in the way of scheduling them?

-

Looking at the modifiable risk factors for cancer (body composition, alcohol, processed meat, physical activity, etc.), which one applies most to you, and what's one small change you could make?

Works cited¶

References¶

-

World Health Organization. Preventing cancer (WHO Activities; unknown). Available at: https://www.who.int/activities/preventing-cancer

-

American Cancer Society. New study finds 40% of cancer cases and almost half of all deaths in the U.S. linked to modifiable risk factors (2024). Available at: https://pressroom.cancer.org/releases?item=1341

-

GBD 2019 Cancer Risk Factors Collaborators. The global burden of cancer attributable to risk factors, 2010-19: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9395583/

-

Zhang Y, Pan X, Chen J, Cao A, Zhang Y, Xia L, et al. Combined lifestyle factors, incident cancer, and cancer mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. British Journal of Cancer. 2020;122(7):1085-1093. doi:10.1038/s41416-020-0741-x

-

WHO Regional Office for Europe. No level of alcohol consumption is safe for our health (2022). Available at: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/04-01-2023-no-level-of-alcohol-consumption-is-safe-for-our-health

-

Rumgay H, Shield K, Charvat H, Ferrari P, Sornpaisarn B, Obot I, et al. Global burden of cancer in 2020 attributable to alcohol consumption: a population-based study. The Lancet Oncology. 2021;22(8):1071-1080. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(21)00279-5

-

Jun S, Park H, Kim U, Choi EJ, Lee HA, Park B, et al. Cancer risk based on alcohol consumption levels: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology and Health. 2023;45:e2023092. doi:10.4178/epih.e2023092

-

Jun S et al. Alcoholic beverage consumption and female breast cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC11629438/

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Obesity and Cancer (2025). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/risk-factors/obesity.html

-

Shi X, Deng G, Wen H, Lin A, Wang H, Zhu L, et al. Role of body mass index and weight change in the risk of cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 66 cohort studies. Journal of Global Health. 2024;14. doi:10.7189/jogh.14.04067

-

Wilson RB, Lathigara D, Kaushal D. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Impact of Bariatric Surgery on Future Cancer Risk. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023;24(7):6192. doi:10.3390/ijms24076192

-

Diao X, Ling Y, Zeng Y, Wu Y, Guo C, Jin Y, et al. Physical activity and cancer risk: a dose‐response analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Cancer Communications. 2023;43(11):1229-1243. doi:10.1002/cac2.12488

-

Yang L, Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM. The Physical Activity and Cancer Control (PACC) framework: update on the evidence, guidelines, and future research priorities. British Journal of Cancer. 2024;131(6):957-969. doi:10.1038/s41416-024-02748-x

-

Hermelink R, Leitzmann MF, Markozannes G, Tsilidis K, Pukrop T, Berger F, et al. Sedentary behavior and cancer: an umbrella review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2022;37(5):447-460. doi:10.1007/s10654-022-00873-6

-

Szablewski L. Insulin Resistance: The Increased Risk of Cancers. Current Oncology. 2024;31(2):998-1027. doi:10.3390/curroncol31020075

-

Clarke CS et al. Associations between glycemic traits and colorectal cancer: a Mendelian randomization analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9086764/

-

Akkız H, Şimşek H, Balcı D, Ülger Y, Onan E, Akçaer N, et al. Inflammation and cancer: molecular mechanisms and clinical consequences. Frontiers in Oncology. 2025;15. doi:10.3389/fonc.2025.1564572

-

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force*. Screening for Breast Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;151(10):716-726. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00008

-

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Colorectal Cancer: Screening (2021). Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/colorectal-cancer-screening

-

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force*. Screening for Prostate Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;149(3):185-191. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-149-3-200808050-00008

-

Hoffman RM, Wolf AMD, Raoof S, Guerra CE, Church TR, Elkin EB, et al. Multicancer early detection testing: Guidance for primary care discussions with patients. Cancer. 2025;131(7). doi:10.1002/cncr.35823

-

American College of Radiology. ACR Statement on Screening Total Body MRI (2023). Available at: https://www.acr.org/News-and-Publications/Media-Center/2023/ACR-Statement-on-Screening-Total-Body-MRI

-

ACOG Committee. Hereditary Cancer Syndromes and Risk Assessment (2019). Available at: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2019/12/hereditary-cancer-syndromes-and-risk-assessment

-

PDQ Cancer Genetics Editorial Board. Genetics of Breast and Gynecologic Cancers (PDQ)–Health Professional Version. National Cancer Institute, 2025. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65767/

-

PDQ Cancer Genetics Editorial Board. Genetics of Colorectal Cancer (PDQ)–Health Professional Version. National Cancer Institute, 2025. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK126744/

-

Park J, Karnati H, Rustgi SD, Hur C, Kong X, Kastrinos F. Impact of population screening for Lynch syndrome insights from the All of Us data. Nature Communications. 2025;16(1). doi:10.1038/s41467-024-52562-5

-

Brown KA, Scherer PE. Update on Adipose Tissue and Cancer. Endocrine Reviews. 2023;44(6):961-974. doi:10.1210/endrev/bnad015

-

Harborg S, Larsen HB, Elsgaard S, Borgquist S. Metabolic syndrome is associated with breast cancer mortality: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2025;297(3):262-275. doi:10.1111/joim.20052